My Life: An Autobiography

Athough I grew up in New York City, as a child I still managed to spend a lot of time in treetops. I’d sit up there watching the people and animals below, the clouds drifting above, and I’d listen to the leaves around me rustling in the wind. I climbed boulders—like the one that inspired Will’s Mammoth and The Boy Who Loved Mammoths. My mother read fairy tales to me from her beloved Book of Knowledge Encyclopedia. It was outdated in many—perhaps most—respects, but the fairy tales in it remained absorbing and timeless. She told me Aesop’s fables. One of our favorites was “The Tortoise and the Hare.” “Slow and steady wins the race,” she would say, “slow and steady.” (As I didn’t write my first book until I was thirty-five, I clearly took the story’s theme to heart.)

I especially wanted to know what the world had been like when my mother was young, before I was born. To think of the world before I existed in it gave everything I looked at—the sun, the trees, a table or chair—a truly odd and mysterious angle. How could these things have existed before I did? Wasn’t this my sun? My trees? My table and chair? I remember, too, lying in bed when she read fairy tales to me. In my mind I could see the great black raven, or the prince riding through the dark forest, or Rapunzel letting down her long, long hair. Yet none of these characters or things were in the room. Where were they then? Often, as I began to fall asleep, I would hear voices murmuring at the edge of my mind, between waking and sleeping. It sounded like many people talking at once. It was as if I was falling asleep on a train filled with passengers or at a party, where conversation was central as cake. I don’t remember ever being able to clearly make out what those voices were saying or even the languages—there seemed to be many—they spoke. Still, words and then, stories, traveled with me into my dreams.

At holidays my father’s extended family would get together and reminisce—at a furious pace—about old times growing up together on New York City’s lower East Side. They were all first generation Russian Jews. Family, a sense of humor, and stories had helped them face hardship. They often told hysterically funny stories but they were not shy about talking about tragedy, either. Those get-togethers made it clear that television was unnecessary, really only a kind of distant “second-best” to what words themselves and a spirited storyteller could bring alive. However, at those family events, whole stories were hardly ever told by any one person. Everyone interrupted everyone else, throwing in pieces, details, contradictions so that the stories grew in concert, en masse, as it were, with all present throwing something of their own into the pot. It was a communal, participatory rite in which each person was both audience and teller, roles switching rapidly back and forth. From my father, who had flown Intelligence and Rescue missions in the Himalayas in World War II, I heard different kinds of stories. His tales were of rescues in the jungles, of rogue elephants, tigers, cobras, and headhunters, of holy men and beggars, and of pilots who flew off on days like any other and never returned. I heard of ancient cities—Calcutta and Bombay—and of mysterious rivers like the Ganges and Brahmaputtra. These were the “stuff” of his tales. I learned, too, how men may die or live by strange turns of fate or chance.

From my grandmothers, who had each left their families at the age of sixteen to come alone to America, fleeing the Revolution, I learned of history’s turmoils, and of the deep, quiet snows of Russian winters long gone by. Violence and conflict had changed and uprooted their lives. Yet in their tales I glimpsed the kind of courage that necessity requires—the willingness to set off on one’s own and find a way through difficulty and danger. In essence, my family gave me what I most wanted and needed—stories. Naturally, I loved to read. My favorite books were myths and legends from around the world, stories about King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table and of Robin Hood as well as any tales of animals. I especially loved Rudyard Kipling’s, The Jungle Books. In sixth grade I found Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick which I devoured in an abridged version, then, shortly after that, in unabridged form, reading it over and over for many years. Moby-Dick became a seminal work for me. From it I learned about whales, work, the sea and the imagination. From it I learned, too, that a masterful storyteller can make you see with your mind and believe what might, at first, have seemed not only improbable but impossible.

I met my wife, Rose, at college. Her family history seemed like an exotic and complex story. Her parents had met on the run—her father fleeing Nazi-occupied Poland and her mother and aunts and grandmother, Yugoslavia. Fate brought them together in an Italian prison. Half the prisoners were sent into Germany and were there, most probably, murdered. The Italian Commander saved the rest by sending them to Albania where Muslim peasants shared with them their own homes and food. Rose was born in a refugee camp in Italy just after the war and came to the United States at age four, speaking Italian, Polish, Yugoslavian, and Yiddish. Through her, new people, stories, words, phrases and expressions came into my life. But it wasn’t until our children, Jacob and Ariya were born, that my interest in sharing literature with children began. (When Jacob was a graduate student in literature at UCLA he was named Poet Laureate of all the California Universities. Ariya received a degree in English literature from the University of Montana in Missoula and went on receive an MFA from the Rochester Institute of Technology.) Through sharing stories each night with them—usually reading aloud but sometimes telling stories—I began to understand how stories, when told in voice, come alive. In those nightly readings I saw that stories pass on archetypal dramas of cause and effect, making values an integral part of our emotional and imaginative thinking. I saw, too, that by getting us to use our minds, indeed, by forcing us to provide our own unique images for each detail, character, and event they reestablish our faith in the creative power of our own imaginations and in the power of wish and dream to guide our lives. I experienced how stories, too, help us stay in touch with the specifics of our own memories and simultaneously discover the universal patterns that run through each and every life. I also found that certain authors had a way of writing that made reading aloud itself an art and a delight. When I read their work I could feel the story coming alive through me. Their tales and their way of telling those tales, nourished the imagination and gave us—our children, Rose, and me—the sense that the story was actually being told. I particularly remember the inspiration I found in reading the work of Howard Pyle, Padraic Colum, Rudyard Kipling, and Isaac Bashevis Singer. I began to feel that I wanted to find some way to do what they had done. I first told stories to a public audience at the Zen Center in Rochester in the mid-1970’s at a traditional, springtime

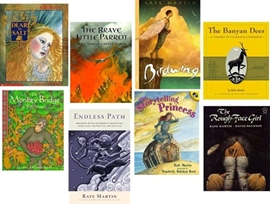

celebration of the Buddha’s birth. A kind of rootedness, a sense of deep and mysterious connection opened for me in those first, wild, story-telling moments. I began to grasp, too, the rich and unpredictable things that voice and gestures could accomplish in molding the actual telling of a tale and in holding the attention of diverse groups. And I saw that the audience itself becomes a vital part of the story process. Each different audience’s linguistic and emotional skills, their attention, energy, background, and understanding may bring out a quite different version of the tale. After that first experience with storytelling I told stories to many other audiences, often in the bookstore that Rose and I ran for ten years. In 1983 I received the Lucille Micheels Pannell Award from the Women’s National Book Association as “the bookseller in the United States and Canada who had been most creative and successful in bringing children and books together.” My first children’s books were published in 1984 and 1985. After that requests for me to tell stories throughout the United States began to arrive. Now, as then, I try to keep a voice alive in my written work. When my books are read aloud I want a reader to feel—like my own children felt when we read the writers we enjoyed most—that a story is actually being told. In the process of writing books I’ve found that I can’t just take a story I tell, write it down, and presto! have a successful book. In working from told story to page I have to take back words and incidents and give the illustrator room to show the story in his or her own way. Over the years I’ve begun to think of the illustrator as my voice and gestures—elements that I depend on in orally telling a tale. And I create scenes specifically for each picture book that never existed in any told version before.

Books, after all, are the intimate experience of a child alone, or of a child and parent, or of a teacher or librarian reading to a small group, and must work differently than a told tale that is typically a social, communal, and live public event. Told tales work directly with the audience’s ability to respond instantly. They thrive on felt emotion—laughter, tears, fear, joy. When written, the pattern of a story and the specific words that build that pattern, take on greater power. Rather than viscerally responding as with the told tale, the reader-listener is led to re-read, to reflect, ponder, and wonder. Each way of telling a story I now see—live telling, storybook, picture book, TV, film, video, and audio recording-each technology we use, offers the storyteller a different mix of quite specific strengths and weaknesses. Each will necessarily create a different emphasis in the story and, so, a different version of the tale. I feel a particular responsibility to each story I choose to recreate as a book. I had very few books as a child and they were treasures to me. Books, too, can last for generations and be shared intimately, parent to child to grandchild. And so, I feel unusually fortunate that I’m able to choose my illustrator for each of my books. If I have no clear idea of who the illustrator should be, (and of course, it remains up to the illustrator to decide, once I’ve selected them, whether he or she will want to do it or not), I discuss different possibilities with my editor until we both hit on the person we feel is right. For me what the book ultimately looks and feels like remains a crucial part of my own work on the tale. However, while I look for an illustrator whose work I enjoy, one whose imagination feels in “sync” with mine and the story’s, I’m not interested in making the illustrator see the story the way I do. Even though I’ve written the book I don’t claim to own the story. For me a good picture book is not just words and pictures but words and pictures resonating together to produce something new. Neither the words nor the pictures stand successfully alone. When I look at my books (I have over twenty out now), I can only say that I’ve been very fortunate in the illustrators who’ve wanted to work with me. We’ve won a lot of awards together. And each has clearly brought their own unique vision to the finished book; each has trusted their own deep sense of storytelling and revealed new levels and relationships in the story. I chose each illustrator, it’s true, but they each did things that were their own, things that I, as the author, would never have imagined. To me that’s what the collaboration between author and illustrator is all about—producing something genuine in its own right and new.

Since I first began telling stories in the mid-seventies I’ve appeared both as a visiting author and as a storyteller in Japan, Hawaii, Alaska, and throughout the continental United States and have been invited to Africa and the Middle East, too. I’ve been featured several times at the National Storytelling Festival in Jonesborough, Tennessee. And I’ve had the wonderful experience of sharing stories I’ve loved with hundreds of thousands of people through my books, as well as by appearing in countless schools, in literary, and educational conferences and storytelling festivals. I remain astonished at my good fortune. Storytellers can only make sounds on the air—that’s all spoken words are. A writer can only make squiggles on paper. Yet those who hear or read those words can see, can feel and live, a whole life in their minds. Though it seems obvious I still enjoy reminding listeners that, if our heads get cut open, no scenes from stories, no characters—no Rough-Face Girl, or boy who lives with the seals, or Will and his mammoth or the boy who rides an eagle’s back—will slide out. All that will be found are bone, blood, and brains. In essence, no one knows, even today, though stories in words are our oldest technology, where the imagination resides. Those characters and their doings are not “in” our heads. Yet through written and told tales, we can nonetheless see them, each in our own unique way, and we can explore and share this deeply human, richly archetypal realm. I can think of nothing more amazing. Every time I tell a story, each time I work on a new book, this mystery lives for me again. When I think about it I can only say that I’ve been very lucky to have the readers and listeners-teachers, librarians, booksellers, parents and children-who make my life’s work possible. Without audiences there are no stories and no storytellers. So, to bring this already long and rambling story to its point: “Thanks!” |

|